Alyssa Aisyah

On this edition of Show Us Your Thesis, Alyssa Aisyah is sharing “The Sacred and The Profane: Restoring Cultural Resilience in Bali” along with what she hoped to achieve with her thesis and her advice for those approaching thesis year in a Covid-19 world.

You can find more of her work here

Below is an description of Alyssa’s thesis.

“The Indonesian island of Bali has established its position as one of the world’s top tourist destinations. Its popularity started in the 1920s when the Dutch colonised Indonesia and successfully cultivated a tourism strategy that has subsequently shaped Bali’s social construct and physical domain. Tourism has replaced agriculture as the main contributor to the local population’s livelihood. And while there is no precursor for resorts as a building type in Balinese tradition, driven by the economics of modern tourism, resort buildings are reshaping the face of the island. This phenomenon has influenced the current touristic culture within the island and has affected the authenticity of Balinese identity, traditions, and values.

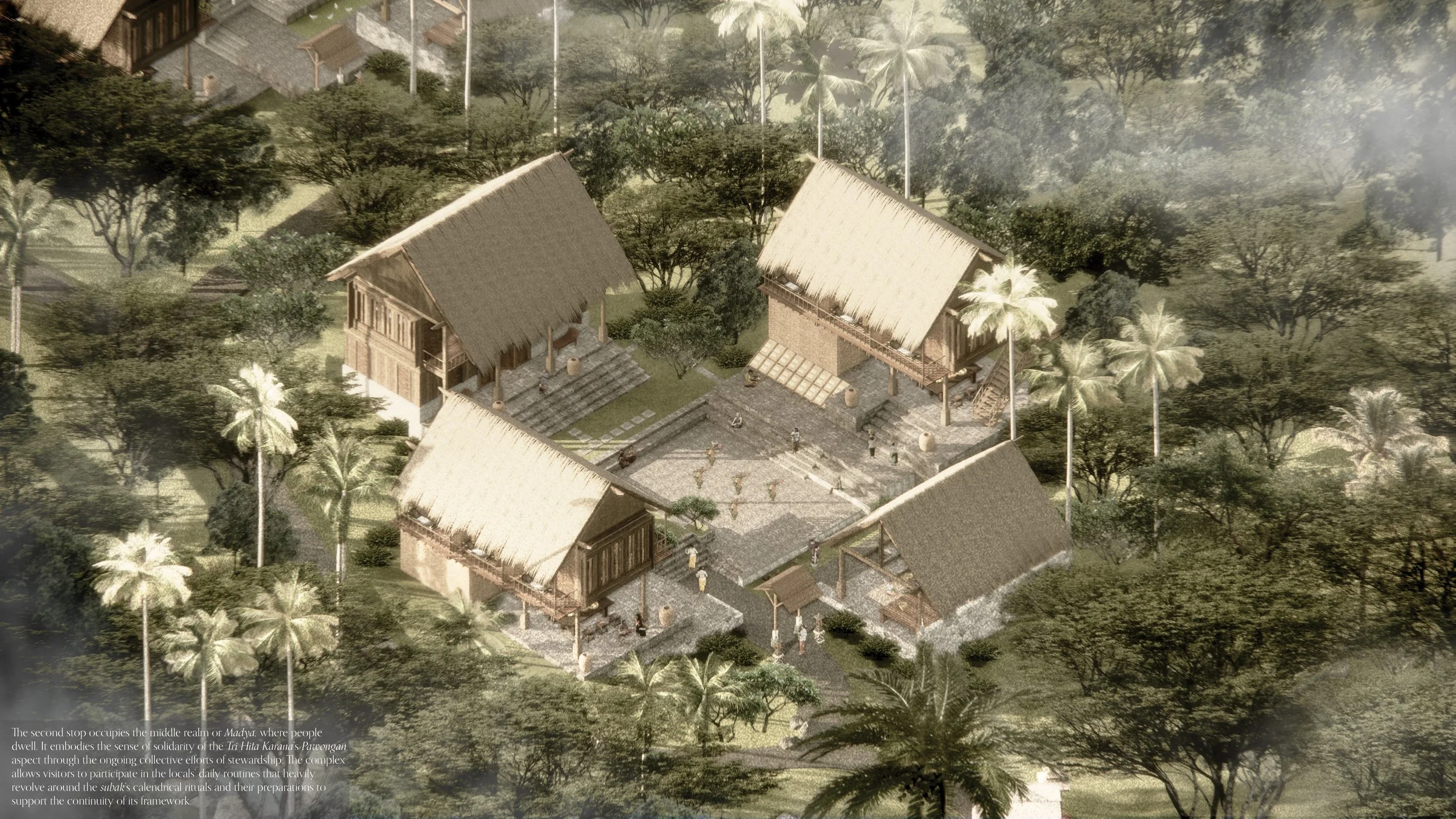

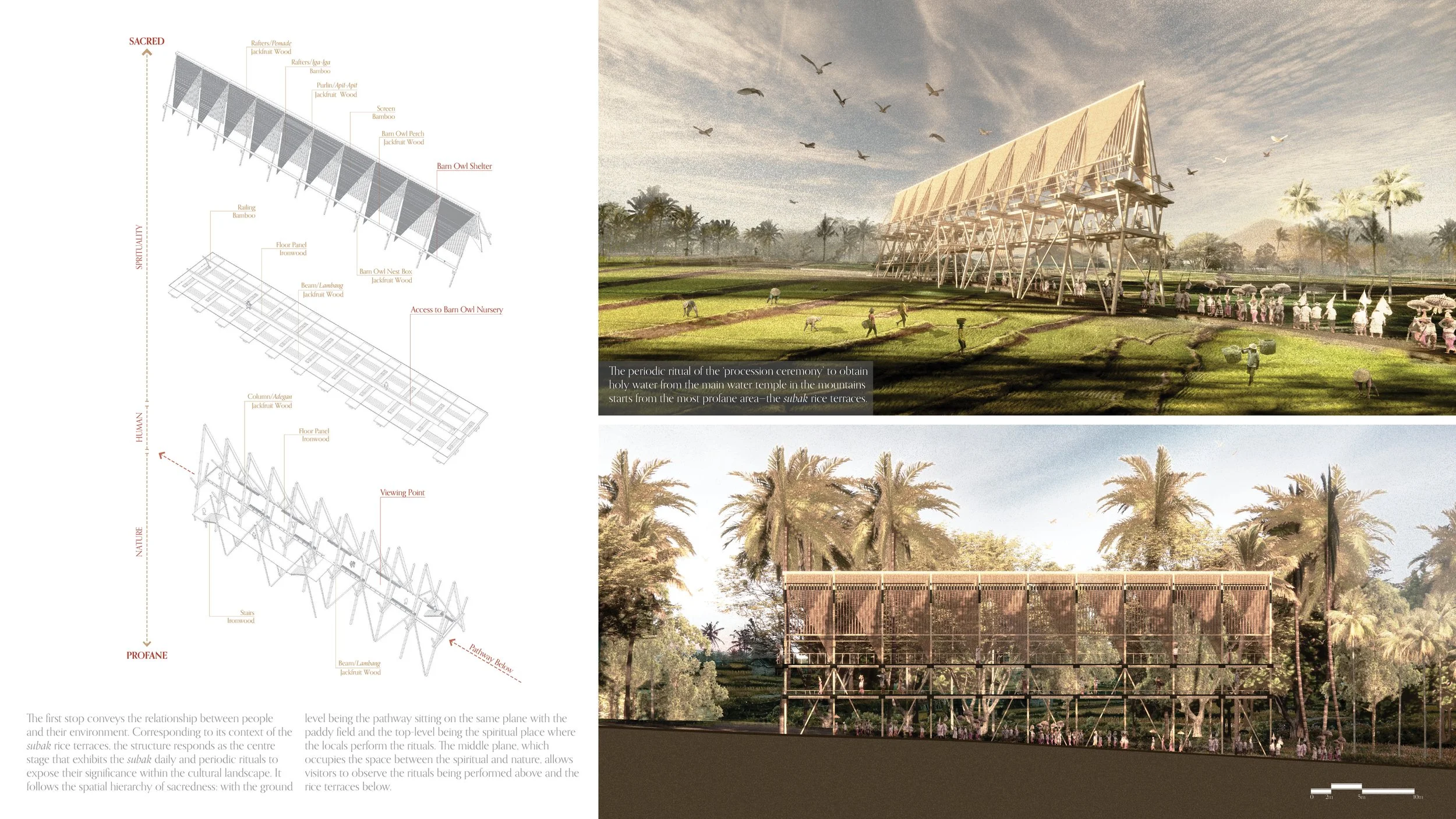

The project addresses the cultural landscape of subak, which encompasses the vast paddy rice terraces, traditional water irrigation system, and its congregation as Bali’s living heritage. Subak is the physical embodiment of Balinese fundamental traditional philosophies of Tri Angga that dictates the tripartite order and creates a hierarchy from the profane to the sacred through its water temple network, and the Tri Hita Karana philosophy, which is embodied in the locals’ rituals and way of life to create harmony and balance within their everyday lives. The project places subak, its system and congregation at its core and implements these two traditional philosophies into the design.

The project proposes three sequences of a journey that echoes the tripartite division of the Tri Angga concept. The project’s framework constructs a cycle that depicts the progression from the profane to the sacred — following the subak’s water temple network along the river. It relies on implementing the regenerative principles of Tri Hita Karana and the subak calendrical rituals to set the course and ensure the continuity of the subak system as Bali’s authentic identity.”

Kia ora, Alyssa! Thank you for sharing your work - What would you say were the key influences when selecting your thesis topic?

When selecting my thesis topic, I’ve always known that I wanted to choose an issue concerning my home country. There are over 1300 ethnic groups in Indonesia, and the Balinese are quite unique because of their long tradition of religious practices rooted in Hinduism and Buddhism (whereas a majority of the country is Muslim).

The ongoing touristic culture and over-tourism in Bali are issues that have steadily altered the island’s identity over the decades. Through this thesis, I wanted to explore how the built environment can facilitate the preservation of local cultural values and practices, and how this can work synchronously with a tourism model that benefits local communities.

Your project looks at Subak, Tri Hita Karana and the Cycle of Progression, and how it is embedded in locals’ everyday life - tell us more!

The cycle of progression is the most fundamental tenet in Balinese culture. It is derived from the traditional Balinese philosophy of Tri Angga—which dictates every element in Balinese cosmology into a tripartite division from the profane to the sacred. On the other hand, Tri Hita Karana becomes the value system that interconnects the tripartite order in Tri Angga through the elements of nature, community, and spirituality.

These elements are interdependent and creates a regenerative cycle that enables well-distributed prosperity, manifesting into daily practices that involve the integration of religion, culture, and tradition. Instead of looking for something new, the project aims to highlight the significance of these values which have existed on the island for centuries.

The project also seeks to go beyond the notion of ‘sustaining’ and into ‘regenerating’, to suggest an alternative model of tourism which encourages the local community to exercise stewardship over their land to counter the prevalence of mass tourism.

The site plan and layout looks at a community living ideology with public spaces and seems to introduce a hierarchy of spaces with the scale of Sacred to Profane. What were the key precedents for this design?

I had a look into international precedents at the start of the project. However, I decided against applying these ideas to the project and instead focused on highlighting values that have been inherently present in the island and the local communities.

From the smallest scale of a traditional house compound to the largest, village compound, the Balinese vernacular served as a crucial reference point for the project. The positioning of elements within Bali’s built environment follows the sacred order of Tri Angga, where every element sits in the correct placement within the island’s spatial hierarchy. An existing traditional village in Bali called Desa Wisata Penglipuran also serves as a reference of how the concept of Tri Hita Karana can be implemented as the backbone of a tourist destination framework by allowing the community to practise environmental and cultural stewardship.

The project proposes a journey through the island’s water temple networks and provides spaces for the community to undertake activities and rituals based on the subak (rice terrace irrigation system) calendrical cycle. It aims to showcase the locals’ community-based activities and promote visibility and the importance of these calendrical rituals to visitors and locals, ultimately preserving their continuity and existence.

The history of resort development also serves as an ‘anti-precedent’ for the project. In the island’s context, it is a typology that mimics the local vernacular, where the reproduction is more seductive than the original. This often creates a misconception among many foreigners over what constitutes the authentic Balinese vernacular and identity.

What were the key decisions made when choosing materiality?

The locality of materials is a key consideration in the project. Bamboo, local river and volcanic stones, rammed earth (often used in subak terraces) are applied in the design. Reclaimed timber is implemented to decrease the demand for newly sourced materials. The use of local materials ties the project to its context and brings a greater sense of familiarity for the local community while responding appropriately to Bali’s climate.

What was the experience of studying during this Covid era? What advice do you have?

The level of uncertainty has been quite challenging – Especially the limited access to resources during lockdowns and constantly switching between online and face-to-face learning. My advice is to always be flexible/adaptable to changes. Not everything will always go as planned, and you often will have to make the best use of the resources available to you at the time. Choosing a supervisor compatible with the way you work is also key. They will greatly facilitate your design process and support you when difficulties arise throughout the process.

And finally, reflecting on your thesis year, what have you learnt generally? Would you change anything?

I have learnt to adapt and tailor my work to changes in circumstances. From the whole process, I’ve also realised that we are often focused on finding new solutions to solve a problem, but in certain situations, the answer can be found through a deeper understanding on ideas and values that are already present.

If there is one thing I could change, I wish I could revisit Bali during my thesis development to experience the traditional practices and ideas I’ve studied through a new perspective, and also immerse myself in the cultural landscape of the subak.

Here’s to hoping you get there soon! Thank you so much, Alyssa and all the best! Ka Kite!

Interview by Sakina Ali